Bra-ket notation

| Quantum mechanics | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Uncertainty principle |

||||||||||||||||

Introduction · Mathematical formulations

|

||||||||||||||||

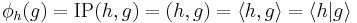

Bra-ket notation is a standard notation for describing quantum states in the theory of quantum mechanics composed of angle brackets and vertical bars. It can also be used to denote abstract vectors and linear functionals in mathematics. It is so called because the inner product (or dot product) of two states is denoted by a bracket,  , consisting of a left part,

, consisting of a left part,  , called the bra (pronounced /ˈbrɑː/), and a right part,

, called the bra (pronounced /ˈbrɑː/), and a right part,  , called the ket (pronounced /ˈkɛt/). The notation was introduced in 1939 by Paul Dirac,[1] and is also known as Dirac notation.

, called the ket (pronounced /ˈkɛt/). The notation was introduced in 1939 by Paul Dirac,[1] and is also known as Dirac notation.

Bra-ket notation is widespread in quantum mechanics: almost every phenomenon that is explained using quantum mechanics—including a large proportion of modern physics—is usually explained with the help of bra-ket notation. It is less common in mathematics.

Contents |

Bras and kets

Most common use: Quantum mechanics

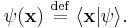

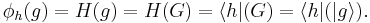

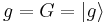

In quantum mechanics, the state of a physical system is identified with a ray in a complex separable Hilbert space,  , or, equivalently, by a point in the projective Hilbert space of the system. Each vector in the ray is called a "ket" and written as

, or, equivalently, by a point in the projective Hilbert space of the system. Each vector in the ray is called a "ket" and written as  , which would be read as "ket psi". (The

, which would be read as "ket psi". (The  can be replaced by any symbols, letters, numbers, or even words—whatever serves as a convenient label for the ket.) The ket can be viewed as a column vector and (given a basis for the Hilbert space) written out in components,

can be replaced by any symbols, letters, numbers, or even words—whatever serves as a convenient label for the ket.) The ket can be viewed as a column vector and (given a basis for the Hilbert space) written out in components,

when the considered Hilbert space is finite-dimensional. In infinite-dimensional spaces there are infinitely many components and the ket may be written in complex function notation, by prepending it with a bra (see below). For example,

Every ket  has a dual bra, written as

has a dual bra, written as  . For example, the bra corresponding to the ket

. For example, the bra corresponding to the ket  above would be the row vector

above would be the row vector

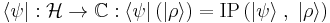

This is a continuous linear functional from  to the complex numbers

to the complex numbers  , defined by:

, defined by:

for all kets

for all kets

where  denotes the inner product defined on the Hilbert space. Here an advantage of the bra-ket notation becomes clear: when we drop the parentheses (as is common with linear functionals) and meld the bars together we get

denotes the inner product defined on the Hilbert space. Here an advantage of the bra-ket notation becomes clear: when we drop the parentheses (as is common with linear functionals) and meld the bars together we get  , which is common notation for an inner product in a Hilbert space. This combination of a bra with a ket to form a complex number is called a bra-ket or bracket.

, which is common notation for an inner product in a Hilbert space. This combination of a bra with a ket to form a complex number is called a bra-ket or bracket.

The bra is simply the conjugate transpose (also called the Hermitian conjugate) of the ket and vice versa. The notation is justified by the Riesz representation theorem, which states that a Hilbert space and its dual space are isometrically conjugate isomorphic. Thus, each bra corresponds to exactly one ket, and vice versa. More precisely, if  is the Riesz isomorphism between

is the Riesz isomorphism between  and its dual space, then

and its dual space, then

Note that this only applies to states that are actually vectors in the Hilbert space. Non-normalizable states, such as those whose wavefunctions are Dirac delta functions or infinite plane waves, do not technically belong to the Hilbert space. So if such a state is written as a ket, it will not have a corresponding bra according to the above definition. This problem can be dealt with in either of two ways. First, since all physical quantum states are normalizable, one can carefully avoid non-normalizable states. Alternatively, the underlying theory can be modified and generalized to accommodate such states, as in the Gelfand-Naimark-Segal construction or rigged Hilbert spaces. In fact, physicists routinely use bra-ket notation for non-normalizable states, taking the second approach either implicitly or explicitly.

In quantum mechanics the expression  (mathematically: the coefficient for the projection of

(mathematically: the coefficient for the projection of  onto

onto  ) is typically interpreted as the probability amplitude for the state

) is typically interpreted as the probability amplitude for the state  to collapse into the state

to collapse into the state

More general uses

Bra-ket notation can be used even if the vector space is not a Hilbert space. In any Banach space B, the vectors may be notated by kets and the continuous linear functionals by bras. Over any vector space without topology, we may also notate the vectors by kets and the linear functionals by bras. In these more general contexts, the bracket does not have the meaning of an inner product, because the Riesz representation theorem does not apply.

Linear operators

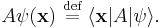

If A : H → H is a linear operator, we can apply A to the ket  to obtain the ket

to obtain the ket  . Linear operators are ubiquitous in the theory of quantum mechanics. For example, observable physical quantities are represented by self-adjoint operators, such as energy or momentum, whereas transformative processes are represented by unitary linear operators such as rotation or the progression of time.

. Linear operators are ubiquitous in the theory of quantum mechanics. For example, observable physical quantities are represented by self-adjoint operators, such as energy or momentum, whereas transformative processes are represented by unitary linear operators such as rotation or the progression of time.

Operators can also be viewed as acting on bras from the right hand side. Composing the bra  with the operator A results in the bra

with the operator A results in the bra  , defined as a linear functional on H by the rule

, defined as a linear functional on H by the rule

.

.

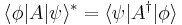

This expression is commonly written as (cf. energy inner product)

Note that the second symbol | is completely optional, i.e.  , since

, since  is in itself a ket and may be written

is in itself a ket and may be written  .

.

If the same state vector appears on both bra and ket side, this expression gives the expectation value, or mean or average value, of the observable represented by operator A for the physical system in the state  , written as

, written as

A convenient way to define linear operators on H is given by the outer product: if  is a bra and

is a bra and  is a ket, the outer product

is a ket, the outer product

denotes the rank-one operator that maps the ket  to the ket

to the ket  (where

(where  is a scalar multiplying the vector

is a scalar multiplying the vector  ). One of the uses of the outer product is to construct projection operators. Given a ket

). One of the uses of the outer product is to construct projection operators. Given a ket  of norm 1, the orthogonal projection onto the subspace spanned by

of norm 1, the orthogonal projection onto the subspace spanned by  is

is

Just as kets and bras can be transformed into each other (making  into

into  ) the element from the dual space corresponding with

) the element from the dual space corresponding with  is

is  where A† denotes the Hermitian conjugate of the operator A.

where A† denotes the Hermitian conjugate of the operator A.

It is usually taken as a postulate or axiom of quantum mechanics, that any operator corresponding to an observable quantity (shortly called observable) is self-adjoint, that is, it satisfies A† = A. Then the identity

holds (for the first equality, use the scalar product's conjugate symmetry and the conversion rule from the preceding paragraph). This implies that expectation values of observables are real.

Properties

Bra-ket notation was designed to facilitate the formal manipulation of linear-algebraic expressions. Some of the properties that allow this manipulation are listed herein. In what follows, c1 and c2 denote arbitrary complex numbers, c* denotes the complex conjugate of c, A and B denote arbitrary linear operators, and these properties are to hold for any choice of bras and kets.

Linearity

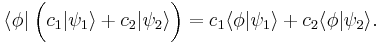

- Since bras are linear functionals,

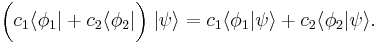

- By the definition of addition and scalar multiplication of linear functionals in the dual space,[2]

Associativity

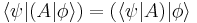

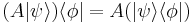

Given any expression involving complex numbers, bras, kets, inner products, outer products, and/or linear operators (but not addition), written in bra-ket notation, the parenthetical groupings do not matter (i.e., the associative property holds). For example:

and so forth. The expressions can thus be written, unambiguously, with no parentheses whatsoever. Note that the associative property does not hold for expressions that include non-linear operators, such as the antilinear time reversal operator in physics.

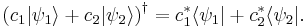

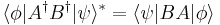

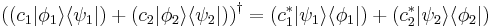

Hermitian conjugation

Bra-ket notation makes it particularly easy to compute the Hermitian conjugate (also called dagger, and denoted †) of expressions. The formal rules are:

- The Hermitian conjugate of a bra is the corresponding ket, and vice-versa.

- The Hermitian conjugate of a complex number is its complex conjugate.

- The Hermitian conjugate of the Hermitian conjugate of anything (linear operators, bras, kets, numbers) is itself—i.e.,

-

.

.

- Given any combination of complex numbers, bras, kets, inner products, outer products, and/or linear operators, written in bra-ket notation, its Hermitian conjugate can be computed by reversing the order of the components, and taking the Hermitian conjugate of each.

These rules are sufficient to formally write the Hermitian conjugate of any such expression; some examples are as follows:

- Kets:

- Inner products:

- Matrix elements:

- Outer products:

Composite bras and kets

Two Hilbert spaces V and W may form a third space  by a tensor product. In quantum mechanics, this is used for describing composite systems. If a system is composed of two subsystems described in V and W respectively, then the Hilbert space of the entire system is the tensor product of the two spaces. (The exception to this is if the subsystems are actually identical particles. In that case, the situation is a little more complicated.)

by a tensor product. In quantum mechanics, this is used for describing composite systems. If a system is composed of two subsystems described in V and W respectively, then the Hilbert space of the entire system is the tensor product of the two spaces. (The exception to this is if the subsystems are actually identical particles. In that case, the situation is a little more complicated.)

If  is a ket in V and

is a ket in V and  is a ket in W, the direct product of the two kets is a ket in

is a ket in W, the direct product of the two kets is a ket in  . This is written variously as

. This is written variously as

or

or  or

or  or

or

Representations in terms of bras and kets

In quantum mechanics, it is often convenient to work with the projections of state vectors onto a particular basis, rather than the vectors themselves. The reason is that the former are simply complex numbers, and can be formulated in terms of partial differential equations (see, for example, the derivation of the position-basis Schrödinger equation). This process is very similar to the use of coordinate vectors in linear algebra.

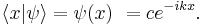

For instance, the Hilbert space of a zero-spin point particle is spanned by a position basis  , where the label x extends over the set of position vectors. Starting from any ket

, where the label x extends over the set of position vectors. Starting from any ket  in this Hilbert space, we can define a complex scalar function of x, known as a wavefunction:

in this Hilbert space, we can define a complex scalar function of x, known as a wavefunction:

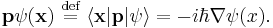

It is then customary to define linear operators acting on wavefunctions in terms of linear operators acting on kets, by

For instance, the momentum operator p has the following form:

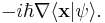

One occasionally encounters an expression like

This is something of an abuse of notation, though a fairly common one. The differential operator must be understood to be an abstract operator, acting on kets, that has the effect of differentiating wavefunctions once the expression is projected into the position basis:

For further details, see rigged Hilbert space.

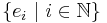

The unit operator

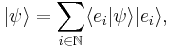

Consider a complete orthonormal system (basis),  , for a Hilbert space H, with respect to the norm from an inner product

, for a Hilbert space H, with respect to the norm from an inner product  . From basic functional analysis we know that any ket

. From basic functional analysis we know that any ket  can be written as

can be written as

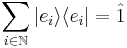

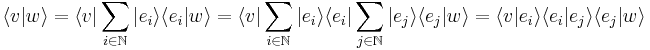

with  the inner product on the Hilbert space. From the commutativity of kets with (complex) scalars now follows that

the inner product on the Hilbert space. From the commutativity of kets with (complex) scalars now follows that

must be the unit operator, which sends each vector to itself. This can be inserted in any expression without affecting its value, for example

where in the last identity Einstein summation convention has been used.

In quantum mechanics it often occurs that little or no information about the inner product  of two arbitrary (state) kets is present, while it is possible to say something about the expansion coefficients

of two arbitrary (state) kets is present, while it is possible to say something about the expansion coefficients  and

and  of those vectors with respect to a chosen (orthonormalized) basis. In this case it is particularly useful to insert the unit operator into the bracket one time or more (for more information see Resolution of the identity).

of those vectors with respect to a chosen (orthonormalized) basis. In this case it is particularly useful to insert the unit operator into the bracket one time or more (for more information see Resolution of the identity).

Notation used by mathematicians

The object physicists are considering when using the "bra-ket" notation is a Hilbert space (a complete inner product space).

Let  be a Hilbert space and

be a Hilbert space and  . What physicists would denote as

. What physicists would denote as  is the vector itself. That is

is the vector itself. That is

-

.

.

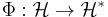

Let  be the dual space of

be the dual space of  . This is the space of linear functionals on

. This is the space of linear functionals on  . The isomorphism

. The isomorphism  is defined by

is defined by  where for all

where for all  we have

we have

-

,

,

Where

are just different notations for expressing an inner product between two elements in a Hilbert space (or for the first three, in any inner product space). Notational confusion arises when identifying  and

and  with

with  and

and  respectively. This is because of literal symbolic substitutions. Let

respectively. This is because of literal symbolic substitutions. Let  and let

and let  . This gives

. This gives

One ignores the parentheses and removes the double bars. Some properties of this notation are convenient since we are dealing with linear operators and composition acts like a ring multiplication.

References and notes

- ↑ PAM Dirac (1982). The principles of quantum mechanics (Fourth Edition ed.). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. p. 18 ff. ISBN 0198520115. http://books.google.com/books?id=XehUpGiM6FIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:quantum+intitle:mechanics+inauthor:dirac&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=mRVsWMu1RsjbysOw2sG2CK_mNpc#PPA20,M1.

- ↑ Lecture notes by Robert Littlejohn, eqns 12 and 13

Further reading

- Feynman, Leighton and Sands (1965). The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. III. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02115-3.

External links

- Richard Fitzpatrick, "Quantum Mechanics: A graduate level course", The University of Texas at Austin.

- 1. Ket space

- 2. Bra space

- 3. Operators

- 4. The outer product

- 5. Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- Robert Littlejohn, Lecture notes on "The Mathematical Formalism of Quantum mechanics", including bra-ket notation.

![|\psi\rangle = [ c_0 \; c_1 \; c_2 \; \dots ] ^T,](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/e64e44c41828214c8e56750fa3592181.png)

![\langle\psi| = [c_0^* \; c_1^* \; c_2^* \; \dots].](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/dd30302fc2a4d8936f08e2b97ecb0892.png)